Race, Equity and Housing: The Early Years

Far-reaching and damaging policies like redlining don’t just materialize on the policy horizon without a powerful series of antecedents. Some of the practices that paved the way for racially explicit housing segregation were born in public housing. This article invites all housing professionals to understand the relationship between the early public housing program and the racial inequity in America today. And as leaders in NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee, we offer this article as an introduction to a new chapter of work. This new chapter will use a learning framework of reading, listening and watching exceptional media content to contribute to a strategic path that will prepare NAHRO, and the larger industry, for meaningful equity work, and subsequent change in housing program and policy.

“America is an old house,” writes Isabelle Wilkerson in her recent New York Times Magazine article “America’s Enduring Racial Caste System”. “The owner of an old house knows that whatever you are ignoring will never go away” and even though you didn’t design or build the house or choose the foundations that are now cracking, you are still responsible. “We are the heirs to whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars, but they are ours to deal with now.”

Wilkerson’s housing metaphor is powerful for us in housing. The practice of housing segregation and racially motivated policy making was widespread in America long before the advent of the first public housing program in 1933. That’s when the federal government showed up in the arena and began a series of policies that perpetuate isolated and segregated neighborhoods and substantial wealth and opportunity gaps that exist to this day. And, while we did not create the policies that caused a chain reaction from which we’ve never recovered as a society, we are their heirs, and we need to understand what we’ve inherited. As advocates, stakeholders and stewards of public housing, we can learn about the part we played in order to better understand how to contribute to the correction of these big, and widening, gaps.

The Public Works Administration and “Neighborhood Composition”

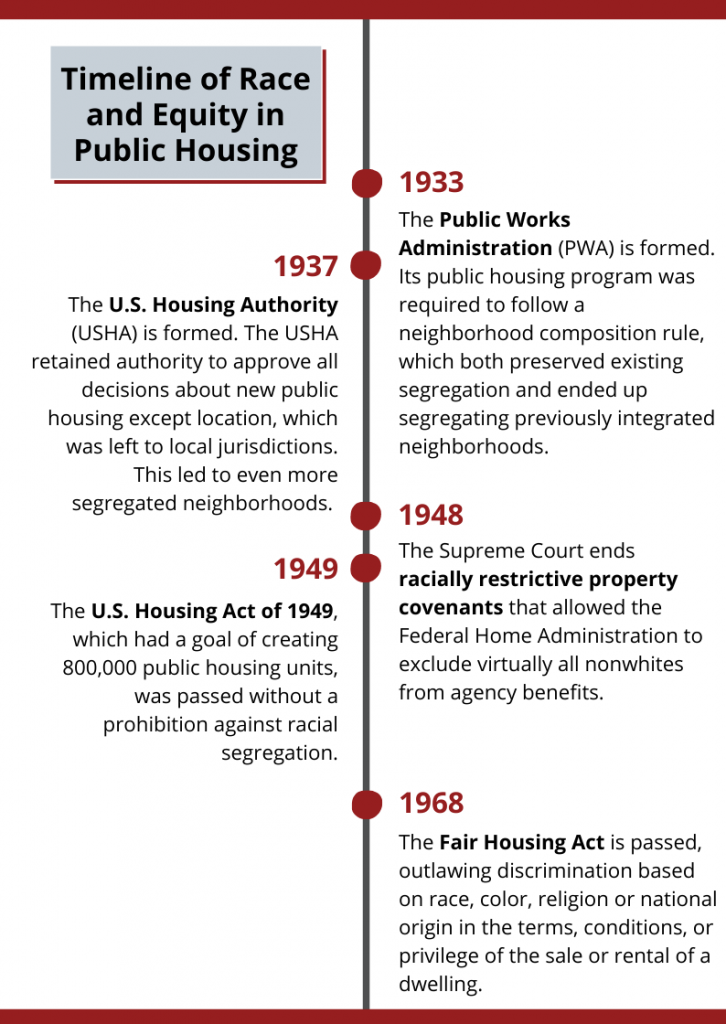

The 1933 program was not the one we know today, but instead its precursor, the Public Works Administration’s housing program. In 1932, Roosevelt was a newly elected president implementing the New Deal vision that won him the presidency. The PWA was a program of the National Industrial Recovery Act, and eventually built 25,000 units of housing in 58 locations over four years. Roosevelt appointed his Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, to manage the public housing program.

In his role, Ickes did several things to reinforce his belief in racial integration and root the new organization in a deep concern for equity. All PWA contracts guaranteed employment for African Americans and included a nondiscrimination clause. Ickes created the office of Racial Relations Services to combat discrimination in housing programs and placed an effective leader at its head.

But despite this foundation, Ickes caved to the politics of the time and approved a policy that would make publicly funded housing explicitly racially segregated. While there is debate about his intentions, history favors the opinion that he was trying to avoid clashes with segregationists and appease a public wary of a government forcing racial integration. Ickes authorized the “neighborhood composition” rule, which meant no new public housing project would alter the racial composition of the neighborhood where it was built.

Despite these segregationist policies, integrated neighborhoods existed during the 1930s, partially because public and private transportation options were so limited that most jobs were located in the central city and people needed to live close to work. But since the PWA had to make a conscious determination whether a neighborhood was “white” or “black” in order to abide by the neighborhood composition rule, integrated neighborhoods often end up segregated. Thus, the neighborhood composition rule perpetuated segregation where it already existed and often created it where it otherwise hadn’t been. As Richard Rothstein writes, “…despite its nominal rule of respecting the prior racial composition of neighborhoods—itself a violation of African Americans’ constitutional rights—the PWA segregated projects even where there was no previous pattern of segregation.” The PWA very often had to make a conscious determination whether a neighborhood was “white” or “black” because integration was an organic pattern in the ‘30s, when private and public transportation options were so limited most jobs were located in the central city and people needed to live close to work.

The first project built by the PWA was Techwood Homes in Atlanta in 1935. To create this 604-unit “whites only” housing, the PWA demolished an integrated neighborhood that was home to 1,600 low-income workers, one-third of whom were African American. The “success” of Techwood Homes not only created a segregated white neighborhood but intensified the housing crisis for African Americans, who then had to crowd into neighborhoods where African Americans were already living. In a further stain on our public housing history the founding documents for most housing authorities carry the mission language of “clearing slum and blight”, which was too often code for demolishing African American neighborhoods to create better housing for whites. The subsequent 24,000 PWA units followed this pattern of maintaining or defining segregation – and worse, maintaining or even exacerbating patterns of lesser opportunity.

The U.S. Housing Authority and Local Jurisdictions

The U.S. Housing Authority, authorized in the U.S. Housing Act of 1937, fully took over PWA building activity by 1939. The USHA left its own imprint on segregation policy by bifurcating the decision-making process for new public housing units: it retained the authority to approve all decisions about tenant selection, tenant eligibility, project budgets and project design but left to the local jurisdiction the ability to decide where to locate this new public housing. This directly led to a system of racially based housing policies that forged segregated neighborhoods for generations.

Allowing local jurisdictions to decide on location meant the discussions of where to situate public housing developments was influenced by fierce resistance from white majorities and weak acquiescence from local politicians who were eager to keep the races segregated. Many of the early public housing communities were built in the worst urban locations and would result in what Kenneth T Jackson describes in Crabgrass Frontier as “the ghettoization of public housing”.

As one observer notes, in the 1940s in Chicago, “local prejudice rather than rational land use has dictated the selection of sites in public housing programs. As the USHA watched Chicago’s decisions about site selection, they evaluated whether they could condition federal aid to Chicago. But, in a showdown between local control and federal authority, the locals won “hands down”. Racially segregated patterns across the nation continued to be created.

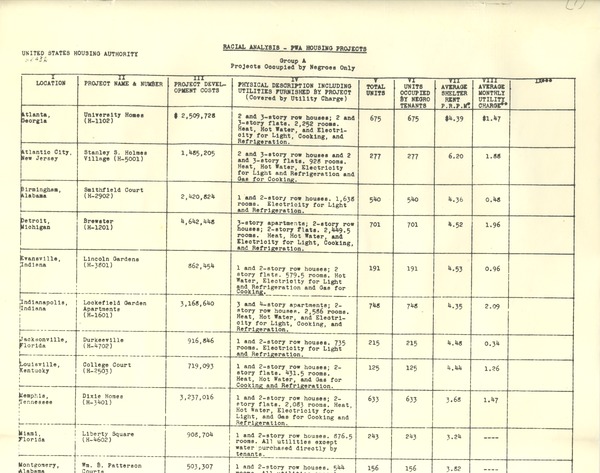

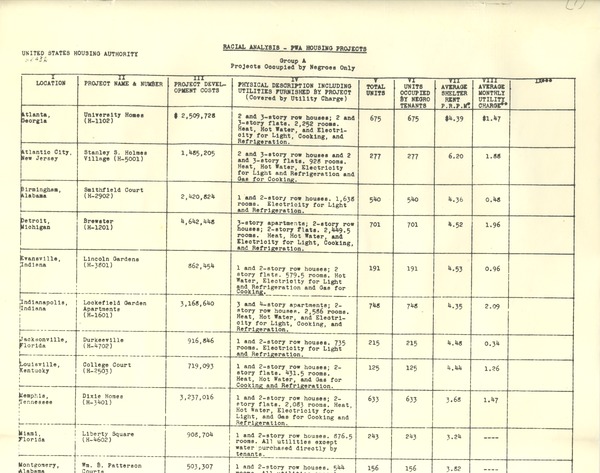

Despite the proliferation of these racist practices, both the PWA and the USHA were conscientious about the doctrine of separate but equal. Both entities sought to create a proportionate number of opportunities for African Americans and tracked the data carefully.

United States Housing Authority Racial analysis – PWA Housing Projects, ca. May 1939

Pruit Igoe: Separate but Equal

St. Louis’ Pruitt Igoe development is perhaps the clearest example of separate but equal. Pruitt Igoe was originally designed to be built on two separate parcels of land: Pruitt was for African American residents in one neighborhood and Igoe was for white residents in another. When the location for Igoe fell through, the St Louis Housing Authority decided to continue to pursue a segregated project by building both buildings on the same land. It took the Supreme Court’s ruling on Brown v Board of Education in 1954 to force the housing authority to change plans once again and imagine Pruitt Igoe as an integrated project.

In the end, Pruitt Igoe evolved into an entirely African American property due to the suburban homeownership opportunities that were available to white families but not to African Americans. As white families fled to greener pastures, the vacancy rate at Igoe became staggering, while the waiting list for Pruitt were tremendously long. Eventually African Americans were admitted to Igoe, and by the mid-1960s it was yet again another fully segregated public housing property.

The expansion of those homeownership opportunities also took place in a highly racialized context. The original system of home appraisal was created by the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which was one of the earliest entities created in the New Deal. HOLC’s appraisal system is understood to have created the practice that became known as redlining. Years later, the Federal Home Administration (FHA)’s adherence to “good business practice” virtually excluded nonwhites from agency benefits by the agency’s insistence on racially restrictive covenants. Those covenants continued in force until 1948, when the Supreme Court’s action put an end to them.

The U.S. Housing Act of 1949 and the Bricker-Cain Amendment

The US Housing Act of 1949 was the next great hope for not only increasing the public housing inventory, with a goal of 800,000 units, but it anticipated being the legislative vehicle to undo the discriminatory practices in housing. Unsurprisingly, the bill provoked intense opposition from the real estate lobby, who had long argued that housing is not an appropriate activity of government.

The opposition was organized by two Republican Senators, John Bricker and Harry Cain, both ardent foes of public housing, who thought they could stop the bill by including what is commonly referred to as a “poison pill”. They inserted a provision that prohibited the practice of racial segregation in public housing. They banked on the theory their amendment would pit northern liberals against southern segregationists, two groups that would otherwise align in support. The Bricker-Cain amendment created turmoil for liberal supporters who had to decide whether it was better for African Americans to have a sweeping housing bill that perpetuated segregation, or no bill at all. In the end, they decided that imperfect housing options are better than no housing options and they organized to defeat the Bricker-Cain amendment.

The failure to include a prohibition against racial segregation in the 1949 Housing Act meant that site selection remained in the hands of local jurisdictions and, not surprisingly, its supporters’ greatest worries were manifest. As Nancy Denton wrote in American Apartheid, “after twenty years of urban renewal, public housing projects in most large cities had become black reservations, highly segregated from the rest of society and characterized by extreme social isolation.”

Public housing continued to be developed in racially explicit patterns that we have yet to recover from. It wasn’t until the 1969 Fair Housing Act that we see genuine attempts to undo the harm.

After the Fair Housing Act

The homeownership programs that grew up around and after public housing and that solidified, and codified, the practice of racially segregated housing is increasingly well understood. Racially explicit covenants, discriminatory mortgage lending, and the redlining of entire neighborhoods are now understood to have created impacts that go well beyond the initial goal of keeping people separate. We bear witness to their disruption of intergenerational upward mobility and its preservation of racial inequality across economic, social, and political sectors. Readers interested in learning more about the policy mistakes and current work to reverse damage done might want to read The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of an Underclass, or watch Brick by Brick and The Pruitt-Igoe Myth.

Having read this brief summary of public housing’s contribution to racially motivated housing policy readers might conclude that now is the time to double down on enforcement of the Fair Housing Act, at a minimum. The Trump Administration’s recent decision to repeal the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule flies in the face of learning from history. When decisions about land use patterns and integrating communities are left to local government, we know what we get. Most American communities retain all, or key, elements of land use patterns that emerged in the early 1900s, and housing policies that evolved during the full height of Jim Crow.

As the effects of the Industrial Revolution settled over American cities, the earliest zoning principles grew up out of a desire to separate uses: carving into separate zones the functions of shopping, homes, jobs, and civic life. Later iterations of functional zoning developed into zoning laws that segregated people explicitly. When the courts intervened, officials skirted the court’s will by separating housing types – a powerfully effective strategy for maintaining the status quo.

Public policies, from housing to transportation, also promoted land use patterns that pushed growth from the center out, separated people and uses, and moved the automobile from a luxury to a necessity. Post-war housing policies of the FHA, and later VA, explicitly favored loans to new single-family development on the edge of existing community over “interior locations” that had a tendency to “lose quality”. These policies were reinforced by public investment that extended infrastructure further and further out, enabling housing to be developed without adjacency to employment and other family supports. This federal investment in the expansion of homogenous suburbs stripped the inner cities of critical infrastructure, physical and social, making education, work and mobility very difficult.

Policy, Equity, and NAHRO

The questions we have for our NAHRO community center around the idea of how we implement policies that truly foster equity that both includes and goes beyond housing access and opportunity. How do we provide truly equal access to quality affordable housing for all eligible Americans, promote equitable housing policy, and assure that housing enables and activates the full potential of all of its residents?

As the working title of our Educate, Innovate, Elevate and Act Subcommittee indicates, our intention is to help educate housing and community development professionals about the roots of social inequity, especially its housing roots; elevate the discussion in NAHRO venues; innovate around anti-racist interventions and then propose a plan to act. We want to hear from you. What do you think the policy strategy for an equitable housing policy includes? With housing as our platform, this is a call to promote policies that preserve and protect our affordable housing communities, ensure the long-term well-being of low-income residents, and create health, economic, environmental and technological equity for all.

The Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee also has a Policy Sucommittee, which is starting the discussion with ideas like greater access to rental housing options; low or no-interest homeownership loans for black, indiginous and people of color (BIPOC); advocacy for inclusionary zoning and source of income discrimination laws that open up housing and education opportunities for low income people and people of color; for full digital access in all affordable housing communities; health-secure and education-ready housing for all young children, . Now is the time to increase and activate tools that improve on the fundamental strategy of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH). Please check NAHRO’s website and social media channels (Twitter, Facebook) for our first event, or contact any of us (see author bios, below).

Author’s Bios

Betsey Martens is co-chair of the Educate, Innovate, Elevate and Act of NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Advisory Committee. She is frequent contributor to the Journal of Housing & Community Development and a past president of NAHRO. She is the former director of Boulder Housing Partners, and currently is working on several ventures to support the housing & community development sector to be active partners in closing achievement, opportunity and equity gaps. Contact Betsey via email.

Elizabeth Glenn is the chair of NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Advisory Committee and a member of NAHRO’s Board of Governors. She retired from local government as the Deputy Director of the Baltimore County Department of Planning where she was responsible for the administration of affordable housing policy and housing finance, community development programs, and homeless services. She is the US Advisor for the UK Nigeria Society for Housing Professionals, President of the Board of Directors of the Bethel Wellness and Empowerment Center in Baltimore City, and is serving her 3rd four-year term as a Trustee of the Maryland Affordable Housing Trust. Contact Liz via email.

Tiffany Mangum is the co-chair of the Educate, Innovate, Elevate and Act Subcommittee of NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Advisory Committee. She is Special Assistant to the CEO of the Fresno Housing Authority and Project Manager for California Ave. Neighborhood, a revitalization project targeting the California Ave. Neighborhood around the historic Edison High School in southwest Fresno. She’s also served 18 years in various human resources roles. A Fresno, Calif. native she is a graduate of Fresno State University where she studied business administration. Contact Tiffany via email.

More Articles in this Issue

Award of Excellence: Parenting Club Night

The Housing Authority of the City of New Britain (NBHA) wins a 2019 Award of Excellence…Award of Excellence: Walking School Bus

The San Antonio Housing Authority (SAHA) wins a 2019 Award of Excellence in Resident and Client…Award of Excellence: SHINE Program Boys & Girls Center

The Housing Authority of the City of Yuma (HACY) wins a 2019 Award of Excellence in Resident and…